The following objects were seen in a wet mount of a concentrated stool specimen from a 50-year-old woman. They measure approximately 50-60 micrometers in greatest dimension. No additional history is available. Identification?

Thanks to Emily and Tony from my lab for taking these lovely photos.

Monday, January 28, 2019

Sunday, January 27, 2019

Answer to Case 529

Answer to Parasite Case of the Week 529: Pollen grains

Congratulations to everyone who wrote in with the correct answer. Most of you recognized this as some type of artifact, with only a few suggesting that these might be helminth eggs. As Old One mentioned, "These structures superficially resemble ascarid eggs. Size, and surface texture would help with differentiation. Toxocara canis is 80-85 micrometers in greatest dimension with a golfball pitted surface texture. T. cat is 65-70 micrometers it also has the golfball pitting but smaller and less distinct then that of T. canis. Baylisascaris procyonis is 63-88 u and has a granular surface texture. I will always checkout surface texture by focusing up and down on the focal plane of an eggs surface. It is surprising the things you'll see. This is how we diagnosed a mixed infection of T. canis and B. procyonis in a dog." (!)

Here is a side-by-side comparison of the pollen in our case and a Toxocara sp. egg. Note also the pores which help to differentiate the pollen grain from a true helminth egg.

I didn't provide a size of the pollen in this case, but estimate the grains to be ~40 micrometers long.

Interestingly, Old one and SilvaB suggested that these might be pollen of the cornflower (Psephellus). I don't know much about pollen, but a quick google search revealed THIS manuscript which has some nice photos of several pollen genera that bear a resemblance to the pollen in this case. Enjoy!

Congratulations to everyone who wrote in with the correct answer. Most of you recognized this as some type of artifact, with only a few suggesting that these might be helminth eggs. As Old One mentioned, "These structures superficially resemble ascarid eggs. Size, and surface texture would help with differentiation. Toxocara canis is 80-85 micrometers in greatest dimension with a golfball pitted surface texture. T. cat is 65-70 micrometers it also has the golfball pitting but smaller and less distinct then that of T. canis. Baylisascaris procyonis is 63-88 u and has a granular surface texture. I will always checkout surface texture by focusing up and down on the focal plane of an eggs surface. It is surprising the things you'll see. This is how we diagnosed a mixed infection of T. canis and B. procyonis in a dog." (!)

Here is a side-by-side comparison of the pollen in our case and a Toxocara sp. egg. Note also the pores which help to differentiate the pollen grain from a true helminth egg.

I didn't provide a size of the pollen in this case, but estimate the grains to be ~40 micrometers long.

Interestingly, Old one and SilvaB suggested that these might be pollen of the cornflower (Psephellus). I don't know much about pollen, but a quick google search revealed THIS manuscript which has some nice photos of several pollen genera that bear a resemblance to the pollen in this case. Enjoy!

Tuesday, January 22, 2019

Case of the Week 528

This week's case was donated by Dr. Lars Westblade. The patient is a middle-aged man who recently returned from Tanzania. He presented with multiple furuncular lesions including the following:

The patient saw a dermatologist who performed a skin biopsy. Here are representative sections (stained with hematoxylin and eosin):

What is the diagnosis?

Sunday, January 20, 2019

Answer to Case 528

Answer to Case 528: Botfly larva; clinical presentation is consistent with furucular myiasis. As Blaine and others have mentioned, "the epidemiology supports this being the 'Tumbu fly', Cordylobia anthropophaga. Cordylobia rodhani is also in Tanzania but less-commonly documented as a source of human myiasis." From a clinical standpoint, the presence of multiple furuncular lesions is also consistent with C. anthropophaga; this fly lays eggs its eggs on soil or damp clothing (e.g. those hanging on a line to dry). The eggs hatch when they come into contact with the skin of the host, and the larvae burrow into the skin to cause furuncles. This is why clothing should be ironed in endemic areas after being taken off the clothes line; ironing destroys the eggs and prevents infection.

Blaine further mentions that the "morphologic features shown in the cuts include the gut, tracheae, and striated musculature. Unlike with tungiasis, eggs are not present as this is a sexually-immature larva. The yellow spines are indeed the cuticular spices; sclerotized chitin (a carbohydrate in the arthropod exoskeleton) usually stains yellow in H&E)."

Unfortunately we don't have the intact larva to identify. Idzi mentioned that "for differentiation of C. anthropophaga from C. rodhani, I’d like to see the spiracular slits as the ones for rodhaini are sinusoidal. Strong pigmentation of the spines suggests anthropophaga though. Rodhaini also is very exceptional..."

Finally, Bernardino, Nema and others mentioned that excision is not necessary for treatment. Instead, the easiest way to remove the larva is to first occlude the opening of the furuncle (through which the larva breathes) with an occlusive substance like petroleum jelly or soap paste (see Case of the Week 408 for a great example of Dermatobia hominis larva removal). After a short period of time, the larva can be removed by simply squeezing the lesion.

Blaine further mentions that the "morphologic features shown in the cuts include the gut, tracheae, and striated musculature. Unlike with tungiasis, eggs are not present as this is a sexually-immature larva. The yellow spines are indeed the cuticular spices; sclerotized chitin (a carbohydrate in the arthropod exoskeleton) usually stains yellow in H&E)."

Unfortunately we don't have the intact larva to identify. Idzi mentioned that "for differentiation of C. anthropophaga from C. rodhani, I’d like to see the spiracular slits as the ones for rodhaini are sinusoidal. Strong pigmentation of the spines suggests anthropophaga though. Rodhaini also is very exceptional..."

Finally, Bernardino, Nema and others mentioned that excision is not necessary for treatment. Instead, the easiest way to remove the larva is to first occlude the opening of the furuncle (through which the larva breathes) with an occlusive substance like petroleum jelly or soap paste (see Case of the Week 408 for a great example of Dermatobia hominis larva removal). After a short period of time, the larva can be removed by simply squeezing the lesion.

Monday, January 14, 2019

Case of the Week 527

This week's case is a good deal more trickier than the last. It was graciously donated by Florida Fan. The patient is a toddler who passed the following 15-cm long worm.

Despite its suggestive outer appearance, the proboscis could not be seen to allow for definitive diagnosis:

Therefore the specimen was sent for histologic sectioning which revealed the following:

In my mind, this is the best use of histologic sectioning for worms - at the direction of the microbiologist, and AFTER the gross specimen has been adequately examined.

Identification?

Despite its suggestive outer appearance, the proboscis could not be seen to allow for definitive diagnosis:

Therefore the specimen was sent for histologic sectioning which revealed the following:

In my mind, this is the best use of histologic sectioning for worms - at the direction of the microbiologist, and AFTER the gross specimen has been adequately examined.

Identification?

Sunday, January 13, 2019

Answer to Case 527

Answer to Parasite Case of the Week 527: Macracanthorhynchus sp., one of the acanthocephalans, or "thorny-headed worms."

Note its relatively large size, and the constrictions that give a false impression of segmentation. My techs call this a bubblegum appearance, which I think you can appreciate in this case:

Macrocanthorhynchus species have a retractable proboscis, which proved to be quite difficult to see in this case. Florida Fan nicely solved this problem by having histologic sections made of the anterior end:

Although I didn't provide enough features for species identification, Florida Fan noted that the morphology is consistent with M. ingens: "The proboscis measures ~500 µm in width and ~650 µm long, much smaller than that of M. hirudinaceus." The geographic distribution (Southeastern United States) also fits with this species. Blaine Mathison, Henry Bishop, Richard Bradbury and others published a very similar case 2 years ago that you can read HERE. It contains a lot of interesting information about the lifecycle, morphologic features and treatment of M. ingens (for example, human infection may be acquired by eating millipedes). Acanthocephalans are more closely related to rotifers than nematodes; hence Blaine's mention of rotifers in the comments.

Florida Fan seems to get a lot of these cases! HERE is one that he donated back in 2013 which nicely shows the eggs of Macracanthorhynchus. You can't tell M. hirudinaceus from M. ingens by its eggs, unfortunately. Take a look at the previous case for more information and a nice poem by Blaine.

Note its relatively large size, and the constrictions that give a false impression of segmentation. My techs call this a bubblegum appearance, which I think you can appreciate in this case:

Macrocanthorhynchus species have a retractable proboscis, which proved to be quite difficult to see in this case. Florida Fan nicely solved this problem by having histologic sections made of the anterior end:

Although I didn't provide enough features for species identification, Florida Fan noted that the morphology is consistent with M. ingens: "The proboscis measures ~500 µm in width and ~650 µm long, much smaller than that of M. hirudinaceus." The geographic distribution (Southeastern United States) also fits with this species. Blaine Mathison, Henry Bishop, Richard Bradbury and others published a very similar case 2 years ago that you can read HERE. It contains a lot of interesting information about the lifecycle, morphologic features and treatment of M. ingens (for example, human infection may be acquired by eating millipedes). Acanthocephalans are more closely related to rotifers than nematodes; hence Blaine's mention of rotifers in the comments.

Florida Fan seems to get a lot of these cases! HERE is one that he donated back in 2013 which nicely shows the eggs of Macracanthorhynchus. You can't tell M. hirudinaceus from M. ingens by its eggs, unfortunately. Take a look at the previous case for more information and a nice poem by Blaine.

Sunday, January 6, 2019

Case of the Week 526

This week's case is a nice straight-forward one - I promise, no tricks! Please identify the following worm. She was ripped in half and only the anterior end was submitted to us. If intact, she would have measured approximately 1 cm long.

Her eggs measured ~60 micrometers in length:

Her eggs measured ~60 micrometers in length:

Saturday, January 5, 2019

Answer to Case 526

Answer: Enterobius vermicularis

As noted by Florida Fan, the diagnostic features shown in this case include the cephalic alae, esophageal bulb, and "D-shaped" eggs (oval with a flattened side). Natalie Ellis described them as 'coffee bean' or 'paper weight' shaped - I had never heard those analogies before!

Thanks to Bernardino Rocha and Silvia for the interesting comments about the different Oxyuroidea found in mammals, reptiles and amphibians (see the comments section on this post for the full details). Thank you also to Old One who reminded us that dogs and cats do not have pinworm and are not the source of your child's infection! I'm amazed that this connection would be made, given how ubiquitous pinworms are. Infection could almost be considered a right of passage in childhood.

Infection is usually diagnosed based on the clinical symptoms (nocturnal pruritus ani) and identification of eggs +/- adult females on the cellulose tape test. Just yesterday I had the privilege of visiting the Meguro Parasitological Museum in Tokyo and got to see their large array of fascinating specimens. Here are a couple of images from their museum:

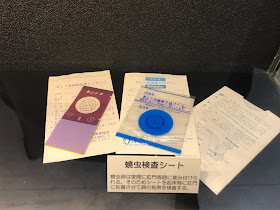

Japanese 'tape prep' kit:

Statistics showing a significant decline in pinworm infections in Japan - likely due to the required annual tape prep exams that are obtained for all school-aged children (see an interesting blog post from a mom on this topic HERE):

And finally, a lovely poem by Blaine:

Dwelling deep down in the lumen of your large intestine

a female pinworm is making her way to the perianal skin

for before the rooster crows

she'll lay eggs in droves

that are going to cause your booty to start itchin'

As noted by Florida Fan, the diagnostic features shown in this case include the cephalic alae, esophageal bulb, and "D-shaped" eggs (oval with a flattened side). Natalie Ellis described them as 'coffee bean' or 'paper weight' shaped - I had never heard those analogies before!

Thanks to Bernardino Rocha and Silvia for the interesting comments about the different Oxyuroidea found in mammals, reptiles and amphibians (see the comments section on this post for the full details). Thank you also to Old One who reminded us that dogs and cats do not have pinworm and are not the source of your child's infection! I'm amazed that this connection would be made, given how ubiquitous pinworms are. Infection could almost be considered a right of passage in childhood.

Japanese 'tape prep' kit:

Statistics showing a significant decline in pinworm infections in Japan - likely due to the required annual tape prep exams that are obtained for all school-aged children (see an interesting blog post from a mom on this topic HERE):

And finally, a lovely poem by Blaine:

Dwelling deep down in the lumen of your large intestine

a female pinworm is making her way to the perianal skin

for before the rooster crows

she'll lay eggs in droves

that are going to cause your booty to start itchin'