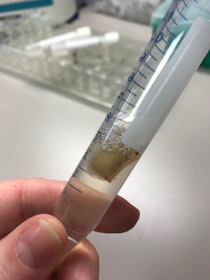

This week's case was donated from Dr. Kamran Kadkhoda. This worm was submitted to the laboratory in saline. It had been seen on the surface of stool from a 3 year old girl.

The following objects were seen within the worm and in the saline submitted with the specimen. They measure approximately 60 micrometers in length.

Identification?

Monday, November 27, 2017

Sunday, November 26, 2017

Answer to Case 470

Answer: Enterobius vermicularis (or E. gregorii); a.k.a. pinworm.

Several of you noted the classic features of the female pinworm shown in this case: the prominent anterior cervical alae, classic eggs (in and outside of the worm), and the slender "pin-like" tail that gives this worm its common name. Males also prominent cervical alae but lack the pointy tail; instead they have a blunt, often curved, posterior end with a single spicule.

As mentioned by Florida Fan, infected patients typically experience nocturnal anal pruritus, and the worm may be observed crawling on the surface of the stool. Ali Mokbel also noted that each work lays approximately 10,000 eggs each day. Importantly, these eggs are fully infectious within 4-6 hours of being laid, and this is one of the most important reasons why this worm is common in the United States and other resource-rich temperate climates. The eggs of most other intestinal nematodes require an incubation period in the soil before becoming infectious, and therefore infection can be prevented with proper sanitation measures, including waste treatment.

Thank you again to Dr. Kadkhoda for donating this classic case!

Several of you noted the classic features of the female pinworm shown in this case: the prominent anterior cervical alae, classic eggs (in and outside of the worm), and the slender "pin-like" tail that gives this worm its common name. Males also prominent cervical alae but lack the pointy tail; instead they have a blunt, often curved, posterior end with a single spicule.

As mentioned by Florida Fan, infected patients typically experience nocturnal anal pruritus, and the worm may be observed crawling on the surface of the stool. Ali Mokbel also noted that each work lays approximately 10,000 eggs each day. Importantly, these eggs are fully infectious within 4-6 hours of being laid, and this is one of the most important reasons why this worm is common in the United States and other resource-rich temperate climates. The eggs of most other intestinal nematodes require an incubation period in the soil before becoming infectious, and therefore infection can be prevented with proper sanitation measures, including waste treatment.

Thank you again to Dr. Kadkhoda for donating this classic case!

Thursday, November 23, 2017

Happy 'Turkey Day'

This is a special post to wish a very happy Thanksgiving to all of my American readers. Can you all see the turkey head in the following blood smear? (you may need to use your imagination a bit).

The image is courtesy of my awesome lab education specialist Emily Fernholz. Can you tell what Plasmodium species is shown here?

The answer to Case of the Week 469 will be posted tomorrow.

The image is courtesy of my awesome lab education specialist Emily Fernholz. Can you tell what Plasmodium species is shown here?

The answer to Case of the Week 469 will be posted tomorrow.

Wednesday, November 22, 2017

Answer to the Turkey Day Tickler

Answer: Plasmodium malariae

Note the small size of the infected red blood cell and 'basket' form of the late-stage trophozoite shown.

Note the small size of the infected red blood cell and 'basket' form of the late-stage trophozoite shown.

Sunday, November 19, 2017

Case of the Week 469

The below was seen on a stool agar culture after incubation at room temperature for several days. The patient is a 62-year-old woman from the Philippines. The images are by my awesome lead tech, Heather Rose, while the video is by Emily Fernholz, Education Specialist extraordinare.

The following were seen in the concentrated wet preparation of the stool specimen :

The following were seen in the concentrated wet preparation of the stool specimen :

Identification?

Saturday, November 18, 2017

Answer to Case 469

Answer: Strongyloides stercoralis. Note the characteristic morphology and the impressive larval load in the stool agar culture! It's been a while since I've seen such a heavily loaded specimen. We immediately contacted the clinical team in this case since we were concerned about potential hyperinfection syndrome - a life-threatening condition - to ensure that the patient was treated immediately.

As mentioned by Florida Fan, Ali, William and Idzi, a rhabditiform larva with a short buccal cavity is clearly shown, allowing us to confirm the identification of S. stercoralis.

Idzi also astutely noted that there are eggs and different stages of larvae present. There were also rare adults in the specimen (not shown). I didn't highlight them in my original post since their morphology is less than optimal, but here are closer views:

Strongyloides stercoralis adults and eggs are not usually seen in stool specimens, but can be seen in very heavy infections like this one.

As mentioned by Florida Fan, Ali, William and Idzi, a rhabditiform larva with a short buccal cavity is clearly shown, allowing us to confirm the identification of S. stercoralis.

Idzi also astutely noted that there are eggs and different stages of larvae present. There were also rare adults in the specimen (not shown). I didn't highlight them in my original post since their morphology is less than optimal, but here are closer views:

Strongyloides stercoralis adults and eggs are not usually seen in stool specimens, but can be seen in very heavy infections like this one.

Monday, November 13, 2017

Case of the Week 468

The week I am re-posting a previous case that was kindly donated by Dr. Julie Ribes. I've chosen to repost the case because it is quite interesting, but also because I have some important new information to share with you about the identification. I'll post the (newly-modified) answer this Friday.

The following material was obtained from an ostomy bag.

Identification?

The following material was obtained from an ostomy bag.

Identification?

Sunday, November 12, 2017

Answer to Case 468

Answer: not a parasite; most consistent with banana material. The twist to this case is that they are NOT actually banana seeds as is commonly taught in parasitology texts. Instead, they are polymerized tannins associated with xylem strands. This information was brought to my attention by Dr. Mary Parker, a microscopist at the Institute of Food Research, Norwich, UK (thank you Mary!). I therefore decided to show this case again so that everyone could benefit from this information.

Here is the full explanation:

The Cavendish bananas that are most often sold in grocery stores do not actually develop seeds. They are naturally sterile (triploid) and can only be propagated vegetatively. However, each aborted ovum has a vascular network consisting of xylem strands and associated cells containing astringent tannins. Upon ripening, the tannins polymerize into a semi-solid mass called 'tannin bodies' which fill the cells. The tannin bodies sometimes incorporate red-brown pigments from polyphenol oxidase activity (like the browning reaction in cut apples) as the cells age, and can therefore be seen as the red-brown bodies in this case. They are associated with the xylem strand which give them a chain-like appearance.

Because I've received some degree of skepticism when I've posted banana material in the past, I decided to conduct an experiment to see if I could recreate their appearance through some laboratory digestion techniques. So here was my process:

Step 1. Sacrifice my banana from lunch for the good of science

Note the darkly-staining structures that are seen in these longitudinal sections. These represent tannin bodies that have darkened over time.

Step 2. Add bananas to pre-prepared tubes of proteinase K in buffer. (Unfortunately I didn't have any amylase which would have digested the carbohydrates in the banana. However, this was the best I could do to simulate the digestive process). Vortex to mix and then incubate at 56 degrees Celsius while gently shaking (the standard tissue digestion that we use for PCR pre-processing).

Step 3. Check regularly. I first checked every 10 minutes , but very quickly realized that this was going to be a long process. After the first 4 hours, this is how the banana sections looked:

Step 4. Check again, 24 hours later - looking pretty good!

Again, it's not a perfect match since the actual patient specimen was subjected to the entire gastrointestinal digestive process. However, the strings of tannin bodies can clearly be seen. Here is how they look microscopically:

I hope you all enjoyed this experiment as much as I did!

Here is the full explanation:

The Cavendish bananas that are most often sold in grocery stores do not actually develop seeds. They are naturally sterile (triploid) and can only be propagated vegetatively. However, each aborted ovum has a vascular network consisting of xylem strands and associated cells containing astringent tannins. Upon ripening, the tannins polymerize into a semi-solid mass called 'tannin bodies' which fill the cells. The tannin bodies sometimes incorporate red-brown pigments from polyphenol oxidase activity (like the browning reaction in cut apples) as the cells age, and can therefore be seen as the red-brown bodies in this case. They are associated with the xylem strand which give them a chain-like appearance.

Because I've received some degree of skepticism when I've posted banana material in the past, I decided to conduct an experiment to see if I could recreate their appearance through some laboratory digestion techniques. So here was my process:

Step 1. Sacrifice my banana from lunch for the good of science

Note the darkly-staining structures that are seen in these longitudinal sections. These represent tannin bodies that have darkened over time.

Step 2. Add bananas to pre-prepared tubes of proteinase K in buffer. (Unfortunately I didn't have any amylase which would have digested the carbohydrates in the banana. However, this was the best I could do to simulate the digestive process). Vortex to mix and then incubate at 56 degrees Celsius while gently shaking (the standard tissue digestion that we use for PCR pre-processing).

Step 3. Check regularly. I first checked every 10 minutes , but very quickly realized that this was going to be a long process. After the first 4 hours, this is how the banana sections looked:

Step 4. Check again, 24 hours later - looking pretty good!

Step 5. Final check - 48 hours. Success! I think that these look nearly identical to our clinical specimen. What do you think?

Close-up view of the tannin bodies and xylem strands (look a lot like the previous cases):Again, it's not a perfect match since the actual patient specimen was subjected to the entire gastrointestinal digestive process. However, the strings of tannin bodies can clearly be seen. Here is how they look microscopically:

Monday, November 6, 2017

Case of the Week 467

This week's post is the second in my new collaboration with the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp and Idzi Potters. The following objects were seen in a urine specimen from a 73 year old man. They measure approximately 150 micrometers in length. The specimen was delayed in getting to the laboratory, and the patient indicated that it was mixed with toilet water.

Identification?

Identification?

Sunday, November 5, 2017

Answer to Case 467

Answer: Schistosoma sp. miracidium. Given the location in urine, the likely species is S. haematobium.

This case from Idzi Potters and the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp shows the characteristic morphology of a form we rarely get to see in the laboratory - the motile ciliated miracidium that hatches from an egg when exposed to water. Note the interesting motility provided by the circumferential cilia.

You can recreate this in the lab by performing the 'hatching test' when you find Schistosoma eggs in stool or urine. There are instructions for the hatching test in most standard parasitology texts, although the process is somewhat time consuming.

In this case, the contamination of the urine specimen with toilet water and the delay in reaching the laboratory likely provided the stimulus and time needed for the eggs to hatch and release miracidia.

The primary differential diagnosis in this case is species of the free-living ciliate, Paramecium, that may be seen in fresh water. Idzi kindly provided the following videos of a Paramecium sp. so that we can appreciate the differences between them and schistosome miracidia. Paramecium spp. may range from 50 to 300 micrometers in length and therefore may overlap with the size range of S. haematobium miracidia (approximately 150 micrometers). They are also covered in circumferential cilia. The primary differences that we can appreciate at this magnification is that they are ovoid, lack an apical papilla (pointed apical end), and have rapid spiraling motility.

One reader suggested that the organisms seen in this case were miracidia from zoonotic schistosomes. This interesting suggestion prompted Idzi and I to do a little research! Idzi was able to find some very helpful studies to show that miracidia are unlikely to survive for more than 24 hours, and therefore couldn't have come from eggs that were passed by another animal and made it into the toilet water. According to Maldonado et al. (Biological studies on the miracidium of Schistosoma mansoni. Am J Trop Med 1948;28:645-657), the average life span of S. mansoni miracidia is 5 to 6 hours. Similarly, Lengy (Studies on Schistosoma bovis [Sonsino 1876] in Israel. Larval stages from egg to cercaria. Bull Res Counc Israel 1962;10:1-36) found that by 24 hours, all of the eggs in their study had hatched and all miracidia were dead. Ozgur Koru also noted that Schistosoma haematobium eggs will quickly hatch once being exposed to water (within 15 minutes). Based on these data, our conclusion is that the miracidia must have come from eggs in the patient's urine that hatched en route to the lab. Luckily the specimen reached the lab in time for the miracidia to be observed in their motile state.

This case from Idzi Potters and the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp shows the characteristic morphology of a form we rarely get to see in the laboratory - the motile ciliated miracidium that hatches from an egg when exposed to water. Note the interesting motility provided by the circumferential cilia.

You can recreate this in the lab by performing the 'hatching test' when you find Schistosoma eggs in stool or urine. There are instructions for the hatching test in most standard parasitology texts, although the process is somewhat time consuming.

In this case, the contamination of the urine specimen with toilet water and the delay in reaching the laboratory likely provided the stimulus and time needed for the eggs to hatch and release miracidia.

The primary differential diagnosis in this case is species of the free-living ciliate, Paramecium, that may be seen in fresh water. Idzi kindly provided the following videos of a Paramecium sp. so that we can appreciate the differences between them and schistosome miracidia. Paramecium spp. may range from 50 to 300 micrometers in length and therefore may overlap with the size range of S. haematobium miracidia (approximately 150 micrometers). They are also covered in circumferential cilia. The primary differences that we can appreciate at this magnification is that they are ovoid, lack an apical papilla (pointed apical end), and have rapid spiraling motility.

One reader suggested that the organisms seen in this case were miracidia from zoonotic schistosomes. This interesting suggestion prompted Idzi and I to do a little research! Idzi was able to find some very helpful studies to show that miracidia are unlikely to survive for more than 24 hours, and therefore couldn't have come from eggs that were passed by another animal and made it into the toilet water. According to Maldonado et al. (Biological studies on the miracidium of Schistosoma mansoni. Am J Trop Med 1948;28:645-657), the average life span of S. mansoni miracidia is 5 to 6 hours. Similarly, Lengy (Studies on Schistosoma bovis [Sonsino 1876] in Israel. Larval stages from egg to cercaria. Bull Res Counc Israel 1962;10:1-36) found that by 24 hours, all of the eggs in their study had hatched and all miracidia were dead. Ozgur Koru also noted that Schistosoma haematobium eggs will quickly hatch once being exposed to water (within 15 minutes). Based on these data, our conclusion is that the miracidia must have come from eggs in the patient's urine that hatched en route to the lab. Luckily the specimen reached the lab in time for the miracidia to be observed in their motile state.

Friday, November 3, 2017

Top 50 Pathology Blogs

Wow, I'm so honored that this blog made it in the list of Top 50 Pathology Blogs:

https://blog.feedspot.com/pathology_blogs/

https://blog.feedspot.com/pathology_blogs/