Answer: Embedded hard tick, partially engorged with blood.

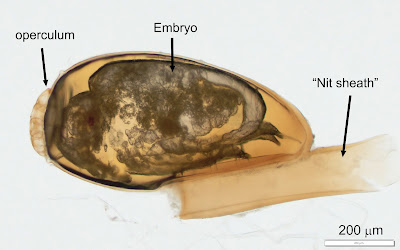

As noted by Florida Fan, it is unfortunate that this tick was sectioned for histopathology, since "we need to examine the anal groove, the shield, the palpi, and the basis capitulum" in order to identify the tick to the genus and species level. This level of identification is helpful for patient management, since different species serve as vectors for different microorganisms. Additionally, finding an engorged Ixodes scapularis in a region of high Lyme disease endemicity may prompt antibiotic prophylaxis in certain situations.

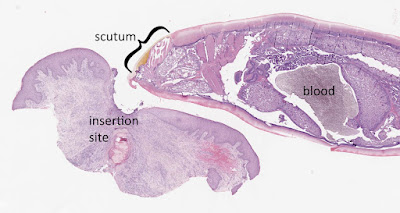

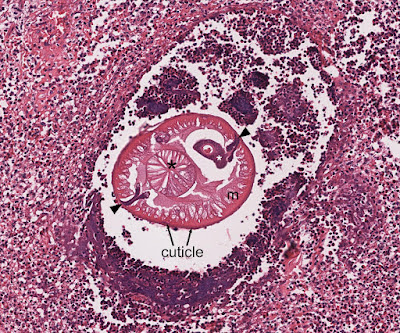

Without being able to examine the external features , we can only make some general comments about the tick in this case. As noted by Richard Bradbury, the tick is engorged, it has a scutum (dorsal shield), and the scutum takes up <1/3 of the body. Thus, we can state that this is a female hard tick. There is also an apparent lack of festoons (although this is hard to assess in sagittal section), and thus the tick may be an Ixodes species. Here are some of the key diagnostic features:

One may ask "why remove the tick like this at all?" Would it have been easier (and much less invasive) to simply remove the tick with tweezers? While I don't know why the tick was removed by excision in this case, I'm guessing that it was misidentified as a thrombosed skin tag.