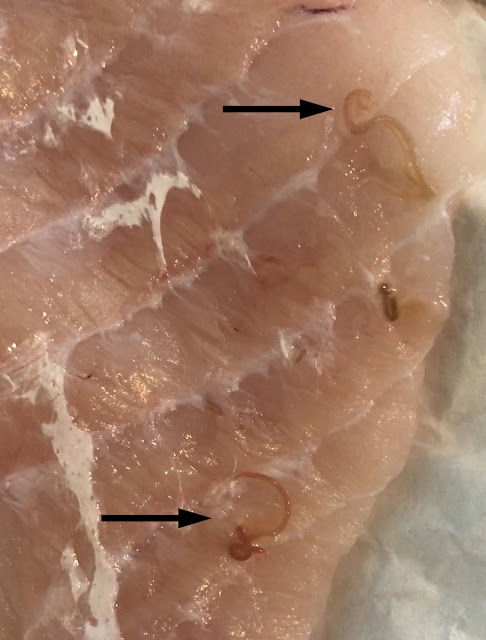

For our last case of May, we have a fun submission from Dr. Megan Shaughnessy. She noted the following in some fresh monkfish she purchased from a small local grocery store. What is the likely identification? Also, what is the risk to humans if ingested?

Tuesday, May 31, 2022

Monday, May 30, 2022

Answer to Case 684

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 684: Anisakid L3 larvae

The following is our third and final discussion from our amazing guest author and 3rd year medical student, Hadel Go. I'm sure you will all agree that her discussions have been among the best we've ever had on this blog. Congratulations on the excellent work, Hadel!

_____________________

Worm cases are always my favorite because the comments are

either “They are so beautiful!!” (@Parasite_Power on Twitter) or “…That’s a

wholelottanope” (Valmik in the comments).

This is a nematode in the Anisakidae family, likely Pseudoterranova or Anisakis spp., the two most common cause of human anisakiasis, as many of you suggested. A third genus, Contracaecum, is also a possibility. Mario George Nascimento and Melinh Luong point out that its dark color implicates Pseudoterranova (vs Anasakis which is usually white/pink/red).

However definitive identification to the genus level requires closer inspection of the intestinal cecum and its positioning as mentioned by Idzi P. in the comments and seen in Case 563 which he donated.

Diagnostic features of Pseudoterranova and Anasakis

spp. include a “mucron… and 3 poorly formed anterior lips with a small boring

tooth” (see Case

157 and Case

557). The table below shows some varying characteristics between the two

more common culprits:

|

Larva |

Anisakis

simplex |

Pseudoterranova

decipiens |

|

Appearance |

White, milky |

Yellow-brown |

|

Dimensions |

19-36mm long;

0.3-0.6mm wide |

25-50mm,

0.3-1.2mm wide |

|

Other

features |

Blunt tail,

long stomach, Y-shaped lateral cords, no cecum |

Anteriorly

directed cecum |

LIFE CYCLE (CDC)

1. Marine mammals defecate into the sea releasing unembryonated eggs

2. Eggs become embryonated in water

3. L2 larvae form in eggs and hatch out

4. Free swimming L2 larvae are ingested by crustaceans and mature into L3

larvae in the hemocoel

5. Fish (any marine fish is susceptible) and cephalopods eat infected

crustaceans

6. Larvae migrate to mesentery and muscle tissues of the new host

7. L3 larvae are transferred from fish to fish until ingested by a marine

mammal

8. L3 larvae molt twice in the mammal and develop into adults which produce

eggs

Anisakiasis occurs when these parasites at the L3 larval stage are ingested

in raw or undercooked saltwater seafood. While some larvae will die following ingestion, or make their way up the esophagus into the oral cavity (much to the dismay of the human host!), they may also attach to the wall of the human esophagus,

stomach, or intestine causing damage or inflammation. Since humans are

incidental hosts, the anisakids do not mature into adults. Symptoms include

abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, distention, diarrhea, blood/mucus in stool,

and mild fever. If a patient is allergic to anisakids, rash, itching, angioedema, or

anaphylaxis can occur (even when the worms are dead). Complications include intestinal obstruction,

peritonitis, and intestinal perforation. Severe immune response following

penetration of intestinal tissue can resemble Crohn’s disease.

These roundworms can be visualized and removed with an

endoscope, confirming the diagnosis. If not removed, they will eventually die and can cause

inflammation. A biopsy can reveal an eosinophilic granuloma containing the dead

nematode. Endoscopic or surgical removal of the parasites is curative. Treatment

with albendazole has been used successfully to kill the worms, although not FDA

approved for anisakiasis. Unembedded worms are usually eliminated by the body within 3

weeks.

Avoid infection by following one of these FDA

recommendations which kills the parasite:

- Cook seafood (145°F or above)

- Freeze at -4°F or below for 7 days

- Blast freeze at -31°F or below until solid and store at -31°F or below for 15

hours

- Blast freeze at -31°F or below until solid and store at -4°F for below for 24

hours

I’ve often been asked if I eat sushi and sashimi knowing the

prevalence of these worms… and the answer is YES, I love Japanese cuisine and I

eat them regularly. All fish intended for raw consumption in the US are

required by the FDA to be frozen as stated above so they should be safe. The

dead parasites may still be on the tissue, but they won’t be infectious. I would

however be more hesitant to eat raw or undercooked fish when traveling to

places where there are less stringent regulations. Ask for sushi/sashimi grade

fish and use your best judgement!

TAXONOMY

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Nematoda (roundworms)

Order: Rhabditida

Family: Anisakidae

Read more:

1. CDC -

Anisakiasis

2. Anisakidosis:

Perils of the Deep | Clinical Infectious Diseases | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

3. Anisakis,

Something Is Moving inside the Fish - PMC (nih.gov)

4. Assessing

the risk of an emerging zoonosis of worldwide concern: anisakiasis - PMC

(nih.gov)

Thank you @leon_metlay on Twitter for sharing this paper:

Intestinal

anisakiasis. Report of a case and recovery of larvae from market fish - PubMed

(nih.gov)

This is my third and final post as a guest blogger here and

I’d like to thank Dr. Bobbi Pritt for the opportunity to learn more about these

creatures and share what I’ve learned with you all!

Monday, May 23, 2022

Case of the Week 683

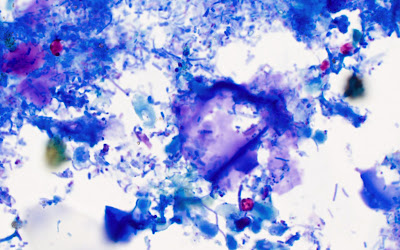

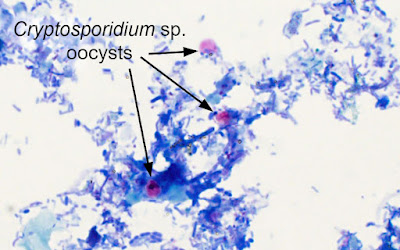

This week's case is from a 4 year old boy with sudden onset of 'explosive' watery diarrhea, accompanied by low grade fever, nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite. A stool specimen was obtained after 1 week of symptoms, and the following objects were noted on a modified acid fast stain. They measure approximately 5 micrometers in diameter.

Here are some questions to consider:

1. What parasite is shown?

2. Name 3 common ways that infection is acquired.

3. What is the typical recommended treatment?

4. What are the risk factors for severe infection.

As with last week, Hadel Go is serving as a guest author, and will help us answer these questions later this week. Stay tuned!

Sunday, May 22, 2022

Case of the Week 683

Answer to Case 683: Cryptosporidium sp. oocysts

The following OUTSTANDING discussion is from our guest author, Hadel Go, a third year medical student with a strong interest in clinical parasitology.

_________________________________________

We received some excellent feedback! Thank you all

for leaving comments on the blog, on Twitter, and on LinkedIn.

Yes, these are Cryptosporidium oocysts. These

protozoans can be identified by their size and consistent red color on modified

acid-fast staining of stool samples. They can also be diagnosed from H&E

stained tissue biopsies (see images here: Cryptosporidium,

parasitewonders.com), but nucleic acid amplification

tests (NAATs) and immunofluorescence microscopy have the greatest

sensitivity and specificity. The two main species that cause infection in

humans are C. parvum and C. hominis, although several others are

also capable. Species identification requires molecular methods like NAAT and/or

sequencing.

Transmission is fecal-oral through food and water

contaminated by stool from an infected person or animal. Some examples include

swallowing pool water, eating unwashed fruits/vegetables from unsafe farms where produce is contaminated with feces containing oocysts (@StephenTristam on Twitter noted a strong association with farming

communities), handling infected farm animals especially calves (@KevKeel brought up

infections among vet students!), caring for an infected person, engaging in

anal sexual contact (as mentioned by @RA_MLS), and touching your mouth with

contaminated hands.

Cryptosporidiosis will present with explosive watery

diarrhea, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting and fever 2-10 days after acquiring

the parasite as seen in our 4-year-old case patient. These are self-limiting in

most immunocompetent individuals. Replenishing fluids and electrolytes to

prevent dehydration is usually sufficient. The infection is mainly concentrated

in the small intestine, but complications can lead to malnutrition and wasting

due to malabsorption or severe dehydration especially in babies.

Immunocompromised patients such as people with

HIV/AIDS, inherited immune diseases, or on immunosuppressive drugs can progress

to severe chronic infection which may become fatal. The respiratory tract can also

be affected (respiratory cryptosporidiosis) resulting in a persistent cough.

Nitazoxanide is the FDA approved treatment for

diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidium in immunocompetent patients ≥ 1 year

of age. However, as Idzi P. mentioned in the comments, “efficacy in

immunocompromised patients is not yet clear… for patients with HIV,

anti-retroviral therapy (to improve immune status) could resolve the symptoms.”

Prevention is essential: practice good hygiene, wash

hands often, do not swallow water when swimming, only drink filtered or treated

water/ice especially when traveling or camping, practice safe sex, do not

consume undercooked meat or unpasteurized milk/apple cider, wash your fruits

and veggies. To avoid recurrent outbreaks, please do not go swimming if you

have diarrhea or within two weeks of resolution of symptoms.

The differential diagnosis is a protozoa in the same

family - Cyclospora cayetanensis (discussed in Case 457). It causes cyclosporiasis which presents similarly

and can be differentiated from Cryptosporidium species by measuring the

oocysts. Their location within enterocytes also varies; see photos from Case 343. The table below compares the two:

|

|

Cryptosporidium parvum |

Cyclospora cayetanensis |

|

Oocyst

size |

4-6

μm |

7.5-10

μm |

|

Acid-fast

staining |

Red

staining (can be variable) |

Often

variable staining |

|

Autofluorescence

under UV |

No

(as pointed out by Idzi P.) |

Yes |

|

Location

in enterocyte |

Replicates

outside the cytoplasm just below the cell membrane |

Replicates

within the cytoplasm |

|

Transmission |

Oocysts

are immediately infectious leading to massive outbreaks |

Person-person

transmission unlikely because sporulation can take weeks and occurs in the

soil. |

DID YOU KNOW?

- Each sporulated oocysts contains 4 sporozoites.

- Cryptosporidium is resistant to chlorine treatments alone due to their

protective outer shell.

- Ultraviolet light and boiling are effective ways to inactivate this protozoan.

- Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts are commonly found in young calves 1-4

weeks old.

- Cryptosporidium zoonotic infection can occur from sheep, cows, pigs,

rodents and other animals.

LIFE CYCLE (3 developmental stages in bold)

1.

Oocysts (thick-walled spore, infective form) are shed in

stool and ingested by host

2.

Excystation releases sporozoites which parasitize

epithelial cells of the GI tract

3.

Meronts undergo asexual multiplication within the brush

border

4.

Gamonts are produced from sexual multiplication

a.

Microgamonts = male; these rupture releasing

microgametes

b.

Macrogamonts = female

5.

Microgametes fertilize macrogamonts forming a zygote

6.

Zygotes give rise to two types of oocysts

a.

Thin-walled oocysts cause autoinfection

b.

Thick-walled oocysts are excreted into the

environment

TAXONOMY

Domain: Eukaryota

Clade: SAR

Infrakingdom: Alveolata

Phylum: Apicomplexa

Order: Eucoccidiorida

Family: Cryptosporidiidae

More information:

1. Parasites - Cryptosporidium (also

known as "Crypto") | Cryptosporidium | Parasites | CDC

2. CDC - DPDx -

Cryptosporidiosis Life Cycle

Thanks to Idzi P. for sharing the following articles

about the 1993 outbreak in Milwaukee, WI (the largest known outbreak affecting

~400,000 people):

1. A Massive

Outbreak in Milwaukee of Cryptosporidium Infection Transmitted through the

Public Water Supply | NEJM

2. Costs of

Illness in the 1993 Waterborne Cryptosporidium Outbreak, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Wednesday, May 18, 2022

Case of the Week 682

This week we have a special guest author, Hadel Go, a medical student (Class of 2024) who is greatly interested in parasitology. I'm very excited that Hadel will be our first ever guest author! The following is our case that she will be teaching us about later this week.

The patient is a young man from Madagascar who presented with a 1-week history of chest pain, night sweats, and fever. Chest X-ray showed a right upper lobe peripheral cavitary lesion. Work up for tuberculosis including AFB stained smears of sputum and sputum PCR using the Xpert MTB/RIF assay were negative. Therefore, a wedge resection of the abscess was performed and revealed the following (H&E stain, 400x original magnification):

What is your diagnosis?Tuesday, May 17, 2022

Answer to Case 682

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 682: Schistosoma mansoni egg.

The following post is from our first ever guest author, Hadel Go. I think you will all agree that Hadel did an outstanding job writing up the answer to the case of the week, and that this is truly one of the best case answers we have had on this blog.

__________________________________

Hadel Go, Medical Student, Guest Author

This is a Schistosoma mansoni egg in lung tissue as many of you correctly identified in the comments. The large lateral spine is a dead giveaway and creates the “quote bubble” morphology mentioned by Jacob @eternalstudying on Twitter. See more images here: Schistosoma mansoni, eggs, tissue (parasitewonders.com).

2. Pulmonary Schistosomiasis – Imaging Features - PMC (nih.gov)

3. Schistosoma mansoni Eggs in Spleen and Lungs, Mimicking Other Diseases - PMC (nih.gov)

4. Frontiers | Schistosomes in the Lung: Immunobiology and Opportunity | Immunology (frontiersin.org)

5. How IVI is confronting schistosomiasis in Madagascar - IVI

6. Madagascar.pdf (stanford.edu)

7. Schistosomiasis (1990): Entire title - YouTube

Tuesday, May 10, 2022

Case of the Week 681

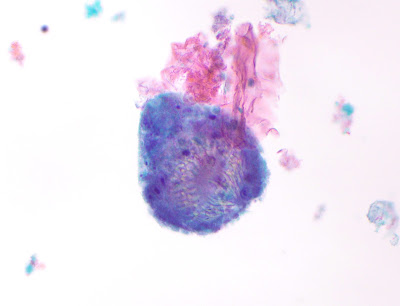

This week's case was generously donated by Tracie Rose from Seattle. The following objects were seen in a Papanicolaou-stained preparation of aspirate fluid from a liver cyst. the patient is from Afghanistan.

Identification?

Monday, May 9, 2022

Answer to Case 681

Answer: Echinococcus sp. invaginated protoscolices

Given the clinical history of a cystic lesion in a patient from Afghanistan, the causative agent is probably E. granulosus.

The protoscolices are somewhat degenerated, but you can still make out the internal row of hooklets:

The protoscolex will evert if ingested by the canine definitive host and form the scolex of the adult tapeworm. Thanks again to Tracie Rose and her lab for donating this case!

If you liked seeing parasites stained with the Papanicolaou (pap) stain, you can also check out this previous case of Schistosoma haematobium eggs in urine. The pap stain is really quite beautiful!

Monday, May 2, 2022

Case of the Week 680

This week's case is from Drs. Harsha Sheorey and Lauren McShane from Australia. The following were seen in bronchial washings from an immunocompromised patient (fluorescent prep for fungi and wet preps):

Here are the culture plates from the bronchial washings.

The patient also has Gram negative bacteremia.

Diagnosis? As a bonus, what forms are we seeing in the respiratory specimens?

Sunday, May 1, 2022

Answer to Case 680

Answer: Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection

This impressive case shows numerous L3 (or possibly L4) S. stercoralis larvae from bronchial washings, and the accompanying culture plates showing bacterial colonies growing in the wake of migrating larvae.

Thanks again to Harsha and Lauren for donating this case!