This week's case was generously donated by Dr. Manohar Mutnal. The following were seen in a peripheral blood smear from a patient with an unknown travel history. What is your differential diagnosis? What additional information would you like?

Monday, June 30, 2025

Monday, June 16, 2025

Case of the Week 779

This week's case was generously donated by Dr. Richard Bradbury. A patient living in The Gambia presented with high fever, body aches, and altered consciousness. Images from the Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood films are shown below.

Due to a shortage of coartem, quinine was administered. Shortly afterwards, the patient's urine turned dark brown:

What is this condition, and what is it caused by?

Sunday, June 15, 2025

Answer to Case 779

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 779: "Black Water fever" - a massive hemolytic event associated with P. falciparum infection and quinine administration.

Black water fever was previously an important cause of death and was prominently reported in British soldiers in the early 20th century. Thankfully, it is rarely seen today with the advent of synthetic antimalarials (e.g., chloroquine) and artemisinin combination therapies. The exact etiology is poorly understood, and seems to be attributed to a complex interaction between the host RBC, the parasite, and antimalarial drugs. It may also occur more often in people with G6PD deficiency.

Tuesday, June 10, 2025

Case of the Week 778

This week's case features the intestinal biopsy of a middle aged man with abdominal pain and diarrhea. The astute pathologist noted these small objects (~20 microns in greatest dimension) associated with ulcerated colonic mucosa. Stain is hematoxylin and eosin (10x, 40x, and 100x objectives). What is your diagnosis?

Sunday, June 8, 2025

Answer to Case 778

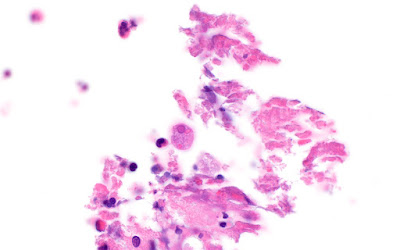

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 778: Amebiasis due to Entamoeba histolytica.

As noted by Dr. Jacob Rattin, "It looks like there is ulceration in the adjacent mucosa and Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites with visibly ingested red blood cells." Several others also noted the ingested RBCs within the trophozoite cytoplasm.

When seen in stool specimens, the presence of RBCs within Entamoeba trophozoites allows us to presumptively call this E. histolytica rather than one of the identical-appearing amebae such as E. dispar. However, in this case, we have another important clue that allows us to presumptively identify the ameba, even if we don't see ingested RBCs: the presence of trophozoites associated with or invading into the ulcerated mucosa. E. dispar is not considered a pathogen, and other doppelgangers (e.g., E. moshkovskii, E. bangladeshi) have not been definitively shown to be pathogenic. Thus, the presence of invasive Entamoeba trophozoites points us towards E. histolytica. Note that the trophozoites look somewhat different in tissue than they do in stool as the central chromatin dot is often not present. However, the outer rim of chromatin is easily visible.

Sunday, May 18, 2025

Case of the Week 777

Dear Readers,

I am excited to announce that we are celebrating our 777th case!

In honor of this milestone, we have a selection of 3 helminth eggs for you to identify. You win the parasite jackpot if you can get all three. There is an 'easy' and 'hard' version, so you get to take your pick.Answer to Case 777

The Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 777 is up - and it's a jackpot of parasite eggs!

Easy version:

- Trichuris trichura

- Ascaris lumbridoides

- Taenia sp.

Hard version:

- Bertiella sp.

- Acanthocephalan egg (M. moniliformis - expressed from the worm so slightly immature, which is why it's not as clear as you would expect)

- Inermicapsifer or Raillietina (Actually Inermicapsifer, but as Idzi mentioned, you cannot tell the egg capsules apart from these two).

How many of you got the jackpot?!?

Thank you for playing for more than 18 years and 777 cases 😉

Saturday, May 17, 2025

Answer to Case 776

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 776: Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. As the name implies, the tachyzoite is the rapidly dividing stage of the parasite (tachy is from the Greek takhus meaning rapid, swift). Tachyzoites invade cells and divide rapidly within parasitophorous vacuoles, ultimately rupturing infected cells. Tachyzoites divide by endodyogeny, an interesting form of replication seen with some coccidia in which two daughter cells develop internally within the parent cell without nuclear conjugation. The parent cell is consumed in the process - yikes!

Shown here is the classic arc-shaped tachyzoite and 2 daughter cells resulting from the process of endodyogeny:

Monday, May 12, 2025

Case of the Week 776

This week's case is a brain biopsy from a middle-aged man with untreated HIV. The specimen appeared necrotic and bloody. Touch preps were made from the material and stained with Giemsa. From the images below taken with the 100x oil objective, what is your diagnosis?

Tuesday, May 6, 2025

Case of the Week 775

This week's case was inspired by Dr. Eric Rosenbaum. Several objects were submitted for parasite identification, including tan-white hair-like structures measuring 30 mm long by <0.2 mm wide. Here is their appearance by light microscopy. How would you sign this case out?

Sunday, May 4, 2025

Answer to Case 775

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 775: Not a parasite. This is actually a hair from my house cat, Walter. Here he is keeping me company while I am trying to update a parasitology chapter:

As noted by Florida Fan, "The objects have neither external nor internal organs. We have a common saying: "No head, no tail, no guts, no parasites”Monday, April 14, 2025

Case of the Week 774

This week's case features another great video from Dr. Rasool Jafari - an object identified from skin scrapings. What is this little arthropod?

Sunday, April 13, 2025

Answer to Case 774

Monday, April 7, 2025

Case of the Week 773

This week's case is generously donated by Dr. Rasool Jafari from the Department of Parasitology and Mycology, School of Medicine, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran. These objects were isolated from a patient and cultured in Modified TYI-S-33 medium. What parasite is this, and what are we seeing here?

Sunday, April 6, 2025

Answer to Case 773

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 773: Giardia duodenalis trophozoites with 'falling leaf' motility. As nicely described by Idzi,this is a "Beautiful video material of Giardia trophozoites! Note that it’s official name now is “Giardia duodenalis”. We used to cultivate these critters on Keisters medium for educational purposes. Not easy though, so the more impressing this video by Dr. Rasool Jafari is! Kudos!"

Indeed, you can make out multiple characteristic features of Giardia trophozoites, including the 'tear drop' shape with 2 nuclei and a central axoneme when viewed anteriorly, a concave spoon-shaped appearance when viewed from laterally, anterior sucking disk, and even some trophozoites dividing by binary fission. I believe I've captured one here but defer to Dr. Jafari for confirmation. Many thanks again to Dr. Jafari for sharing this interesting case with us.

Monday, March 31, 2025

Case of the Week 772

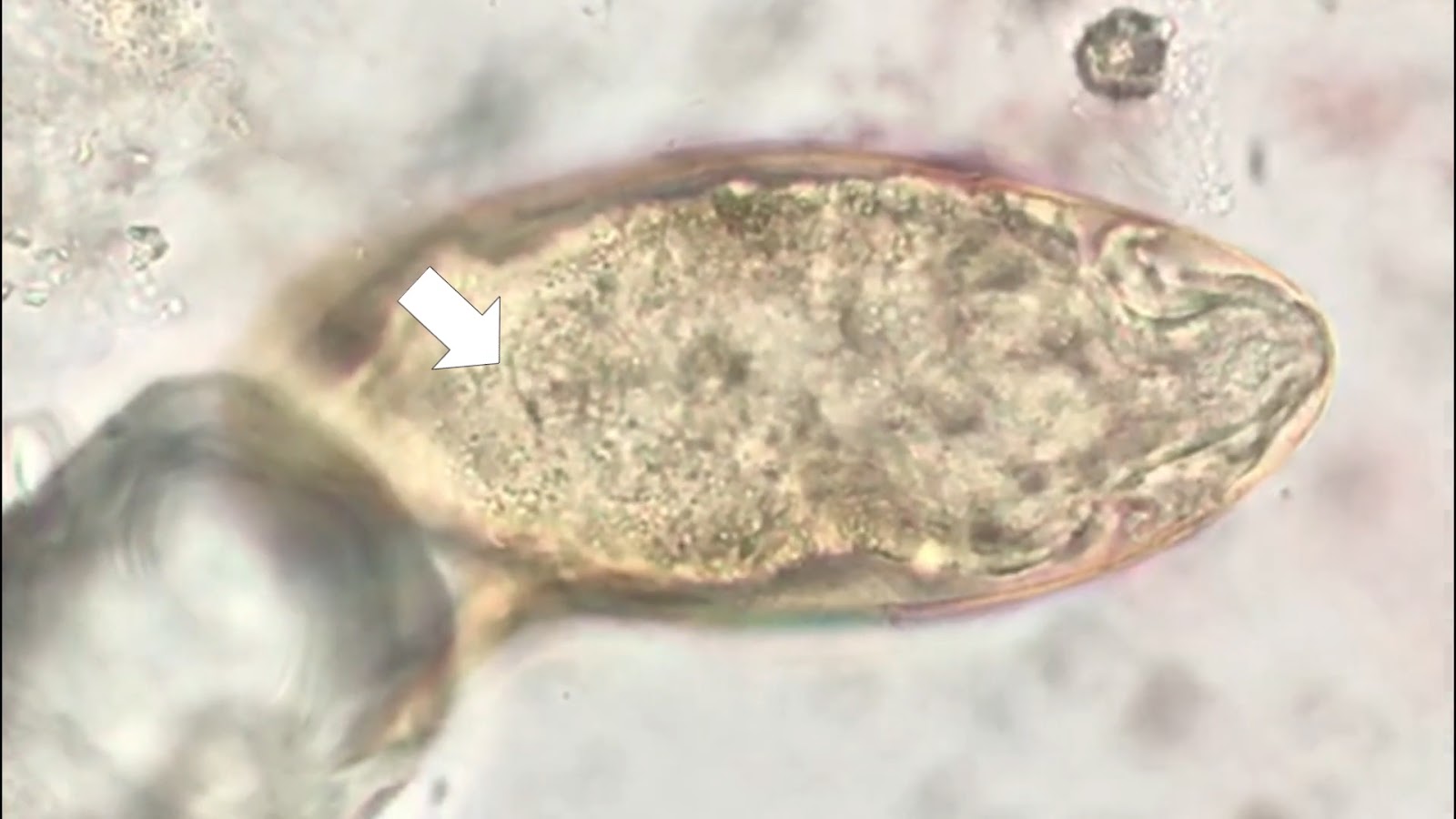

This week's case is generously donated by Dr. Evis Nushi who identified the following structure in direct microscopy of skin scrapings. What is seen here?

Sunday, March 30, 2025

Answer to Case 772

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 772: Demodex folliculorum

This little mite, also known as the follicle mite, is a common skin commensal and incidental finding in this case. I initially thought it was a larva emerging from an egg, but on closer examination realized that it is a more mature form (with 8 legs rather than the 6 found in the larval stage) and that it's posterior end is twisted around. I've done my best to demonstrate this here:

Thanks again to Dr. Evis Nushi who donated this fun case!Tuesday, February 25, 2025

Case of the Week 771

This week's case was generously donated by Dr. Emily Snaverly. The following images show an incidental finding from screening colonoscopy, measuring approximately 1cm long. The patient is an asymptomatic, middle-aged male with no known travel history whose previous colonoscopy did not show any parasites. What is your identification?

Sunday, February 23, 2025

Answer to Case 771

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 771: Rodentolepis (Hymenolepis) nana, the dwarf tapeworm

As nicely described by Florida Fan, Idzi Potters, and Menzler, the craspedote positioning of the proglottids, armed rostellum, and characteristic (although immature) eggs with prominently splayed, large hooklets all point to R. nana. If you look very closely, you can make out the polar filaments:

Thanks again to Dr. Snaverly for donating these beautiful photos!Monday, February 17, 2025

Case of the Week 770

This week's case is from Idzi Potters and the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp. The following structures were seen in a stool specimen from a child living in a rural area of Laos. They measure approximately 60 micrometers in greatest dimension. What is your identification?

Sunday, February 16, 2025

Answer to Case 770

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 770: Schistosoma mekongi

The following excellent discussion is by our guest author, Dr. Asra Hasan:

This week’s answer is Schistosoma mekongi! With that, we’ve shown a Schistosoma trio already for the new year—S. haematobium, S. mansoni, and now S. mekongi. Great job, Florida fan! You correctly spotted the inconspicuous lateral spine and the internal miracidium of S. mekongi. And a shoutout to our anonymous writer—your answer was pretty close, as S. mekongi looks a lot like S. japonicum, just smaller, and with a slightly different geographic range.

The endemic area for S. mekongi is along the lower Mekong River—Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia—hence, the population at risk is comparatively smaller than for other Schistosoma species.

Have a read of the clinical vignette below:

“A 42-year-old male rice farmer from a rural village in Cambodia presents to a local clinic with complaints of chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, and progressive weight loss over the past six months. He also reports intermittent fever and generalized weakness. On examination, he has hepatosplenomegaly and mild ascites. Laboratory results reveal eosinophilia, and stool microscopy shows small, subspherical eggs with a minute lateral spine at one end. The patient has frequent exposure to river water while working in the fields.” And that would qualify as a typical case for this week—S. mekongi!

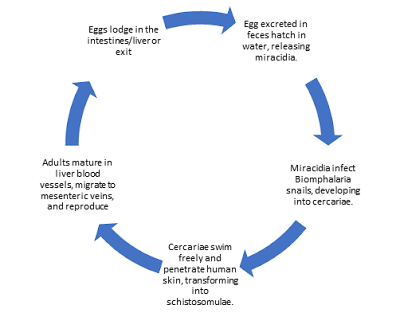

The life cycle is similar to other Schistosoma species discussed on this blog (for example, Case 766), except that the definitive hosts are both humans and dogs, and the intermediate host is the snail Neotricula aperta. S. mekongi primarily affects the intestines, liver, and spleen, and rarely, disseminated sites such as the brain.

Diagnosis

Microscopic examination of stool after sedimentation concentration is used to detect eggs.

Antigen tests: Point-of-care lateral flow assays detecting CCA are used for field screening. In the lab, ELISA has been used to detect circulating schistosome antigens in serum and urine and may be the preferred method for confirming diagnosis. Since stool examination can detect schistosome eggs weeks after cure, detection of circulating antigens (CAA & CCA) in blood or urine provides evidence of an ongoing active infection, as both antigens are rapidly cleared from circulation.

Antibody tests can detect evidence of infection, but cannot distinguish current from past infection, and are not particularly useful due to cross-reactions with other helminth infections.

Treatment

Praziquantel is the drug of choice.

Prevention of schistosomiasis involves universal treatment campaigns and that has shown dramatic decrease in disease burden although it has not been helpful in eliminating the disease completely requiring repeated campaigns. Travelers can prevent schistosomiasis by avoiding bathing, swimming, wading, or other contact with freshwater in disease-endemic countries.

And finally, a mention about the World Health Organization. The World Health Organization's roadmap for eliminating neglected tropical diseases recommends targeting Schistosoma mekongi for elimination. Current strategies in affected communities include: Preventive chemotherapy targeting at-risk populations (e.g., entire villages along the Mekong) and distribution of information and education, improvements in water, sanitation, and hygiene.

Some more reading:

CDC resources: https://www.cdc.gov/schistosomiasis/resources/

Monday, February 3, 2025

Case of the Week 769

Sunday, February 2, 2025

Answer to Case 769

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 769: Live Schistosoma mansoni ova. Note the motile miracidium with its characteristic 'flame cell' - a specialized cell that is part of its excretory system, characterized by a flickering, flame-like movement of cilia which helps to expel waste products from the egg (see image below, and be sure to check out the video HERE.

The following excellent discussion is written by our guest author, Dr. Azra Hasan:

Everyone rightly recognized the oval egg with a” lateral spine”, the hallmark feature of Schistosoma mansoni.

Sometimes, it may be necessary to tap the coverslip to move the eggs; the lateral spine may not be visible if the egg is turned on its side. In very light or chronic infections, eggs may be tough to detect in stool; therefore, multiple stool examinations may be required and a biopsy and/or immunologic tests for antigen or antibodies help diagnose infection in these patients.

Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharziasis) spreads when people come in contact with freshwater contaminated by microscopic swimming cercariae released from infected snails. These cercariae penetrate intact skin and mature into adult worms as shown in the life cycle below. Schistosoma mansoni is endemic in Africa, South America, and the Caribbean. Humans are the definitive host and snails (Biomphalaria spp.). are the intermediate hosts. Adult worms reside in blood vessels of the intestines, laying eggs that trigger inflammation, fibrosis, and organ damage.

Clinical features

- Acute:

- Cercarial dermatitis follows skin penetration by cercariae. Stronger reactions may be seen in previously-sensitized hosts.

- Katayama fever is characterized by fever, cough, malaise, and diarrhea (Acute hypersensitivity reaction to the migrating larvae of S. mansoni, also seen in S. japonicum and S. mekongi)

- Chronic:

- Eggs are deposited in the mesenteric venous system and enter the intestinal wall and liver where they trigger an eosinophilic granulomatous host response, resulting in bloody diarrhea.

- While some eggs are excreted in the stool, many remain trapped in the tissue.

- Over time, chronic inflammation leads to fibrotic changes in the liver, with rigid portal veins, and portal hypertension with hepatomegaly.

- Rarely, schistosomiasis may present as neuroschistosomiasis (seizures, paralysis) due to ectopic eggs (usually associated with S. japonicum).

Fun Facts:

- Schistosoma is an ancient foe. Schistosoma eggs were found in 3000-year-old Egyptian mummies!

- Clingy Couple: We have seen the female worm residing in the male’s gynecophoric canal. Did you know this is a lifelong “embrace”?

- Undercover agent: These parasites coat themselves in human proteins to hide from the immune system.

- Egg factory: A female S. mansoni will produce ~300 eggs per DAY

Treatment:

Praziquantel is the gold standard. Oxamniquine is effective only against S. mansoni. Resistance to both these drugs has been reported. Early treatment prevents portal hypertension and related complications

Prevention with improved sanitation and avoiding wading in insanitary water, is better than cure! (Praziquantel kills adult worms but not immature larvae- It is important to note that If treatment starts early, always follow up with retreatment).

Salmonella-schistosome syndrome: When a secondary bacterial infection (usually Salmonella) occurs, anti-schistosome and antibacterial therapy should be given together; the disease remains if the schistosome is not treated simultaneously.

Some interesting case reports:

- Ectopic Eggs: Hepatic granulomas mimicking cancer in a Brazilian man (DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1436).

- Cardiac Schistosomiasis: A rare case of a 25-year-old man in Ethiopia with chest pain and heart failure was found to have S. mansoni eggs in myocardial tissue during autopsy. (PMID:32534906)

- Schistosoma Appendicitis- A case report of a 12-year-old Kenyan boy with acute appendicitis who had his appendix packed with S. mansoni eggs. (PMID 34840930)

- Pulmonary Hypertension- A 35-year-old Brazilian woman with chronic cough and fatigue had S. mansoni eggs in lung biopsies, leading to severe pulmonary hypertension DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2019.PA5392

- The Traveler’s Nightmare- A German backpacker developed acute neuroschistosomiasis after swimming in the Nile. MRI showed spinal cord inflammation from ectopic eggs! (PMID:29232415)

- Rectal Prolapse in a Child: A 4-year-old Ethiopian girl with chronic rectal prolapse had S. mansoni eggs in rectal biopsies. Parasites weaken tissues over time! (PMID:31462942)

- Paste the PMID number in PubMed for full-text articles

- Type ‘Schistosoma’ in the search bar of this blog and walk through the pages for more images and reads.

Monday, January 27, 2025

Case of the Week 768

This week's case was generously donated by Dr. Mike Mitchell. The following organism was found in the agar of a bacterial urine culture. It is about 1.5 mm in greatest dimension. Would you report this finding, and if so, how?

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)