This week's case was generously donated by Dr. Emily Snaverly. The following images show an incidental finding from screening colonoscopy, measuring approximately 1cm long. The patient is an asymptomatic, middle-aged male with no known travel history whose previous colonoscopy did not show any parasites. What is your identification?

Tuesday, February 25, 2025

Sunday, February 23, 2025

Answer to Case 771

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 771: Rodentolepis (Hymenolepis) nana, the dwarf tapeworm

As nicely described by Florida Fan, Idzi Potters, and Menzler, the craspedote positioning of the proglottids, armed rostellum, and characteristic (although immature) eggs with prominently splayed, large hooklets all point to R. nana. If you look very closely, you can make out the polar filaments:

Thanks again to Dr. Snaverly for donating these beautiful photos!Monday, February 17, 2025

Case of the Week 770

This week's case is from Idzi Potters and the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp. The following structures were seen in a stool specimen from a child living in a rural area of Laos. They measure approximately 60 micrometers in greatest dimension. What is your identification?

Sunday, February 16, 2025

Answer to Case 770

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 770: Schistosoma mekongi

The following excellent discussion is by our guest author, Dr. Asra Hasan:

This week’s answer is Schistosoma mekongi! With that, we’ve shown a Schistosoma trio already for the new year—S. haematobium, S. mansoni, and now S. mekongi. Great job, Florida fan! You correctly spotted the inconspicuous lateral spine and the internal miracidium of S. mekongi. And a shoutout to our anonymous writer—your answer was pretty close, as S. mekongi looks a lot like S. japonicum, just smaller, and with a slightly different geographic range.

The endemic area for S. mekongi is along the lower Mekong River—Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia—hence, the population at risk is comparatively smaller than for other Schistosoma species.

Have a read of the clinical vignette below:

“A 42-year-old male rice farmer from a rural village in Cambodia presents to a local clinic with complaints of chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, and progressive weight loss over the past six months. He also reports intermittent fever and generalized weakness. On examination, he has hepatosplenomegaly and mild ascites. Laboratory results reveal eosinophilia, and stool microscopy shows small, subspherical eggs with a minute lateral spine at one end. The patient has frequent exposure to river water while working in the fields.” And that would qualify as a typical case for this week—S. mekongi!

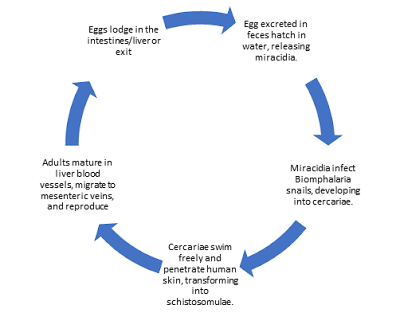

The life cycle is similar to other Schistosoma species discussed on this blog (for example, Case 766), except that the definitive hosts are both humans and dogs, and the intermediate host is the snail Neotricula aperta. S. mekongi primarily affects the intestines, liver, and spleen, and rarely, disseminated sites such as the brain.

Diagnosis

Microscopic examination of stool after sedimentation concentration is used to detect eggs.

Antigen tests: Point-of-care lateral flow assays detecting CCA are used for field screening. In the lab, ELISA has been used to detect circulating schistosome antigens in serum and urine and may be the preferred method for confirming diagnosis. Since stool examination can detect schistosome eggs weeks after cure, detection of circulating antigens (CAA & CCA) in blood or urine provides evidence of an ongoing active infection, as both antigens are rapidly cleared from circulation.

Antibody tests can detect evidence of infection, but cannot distinguish current from past infection, and are not particularly useful due to cross-reactions with other helminth infections.

Treatment

Praziquantel is the drug of choice.

Prevention of schistosomiasis involves universal treatment campaigns and that has shown dramatic decrease in disease burden although it has not been helpful in eliminating the disease completely requiring repeated campaigns. Travelers can prevent schistosomiasis by avoiding bathing, swimming, wading, or other contact with freshwater in disease-endemic countries.

And finally, a mention about the World Health Organization. The World Health Organization's roadmap for eliminating neglected tropical diseases recommends targeting Schistosoma mekongi for elimination. Current strategies in affected communities include: Preventive chemotherapy targeting at-risk populations (e.g., entire villages along the Mekong) and distribution of information and education, improvements in water, sanitation, and hygiene.

Some more reading:

CDC resources: https://www.cdc.gov/schistosomiasis/resources/

Monday, February 3, 2025

Case of the Week 769

Sunday, February 2, 2025

Answer to Case 769

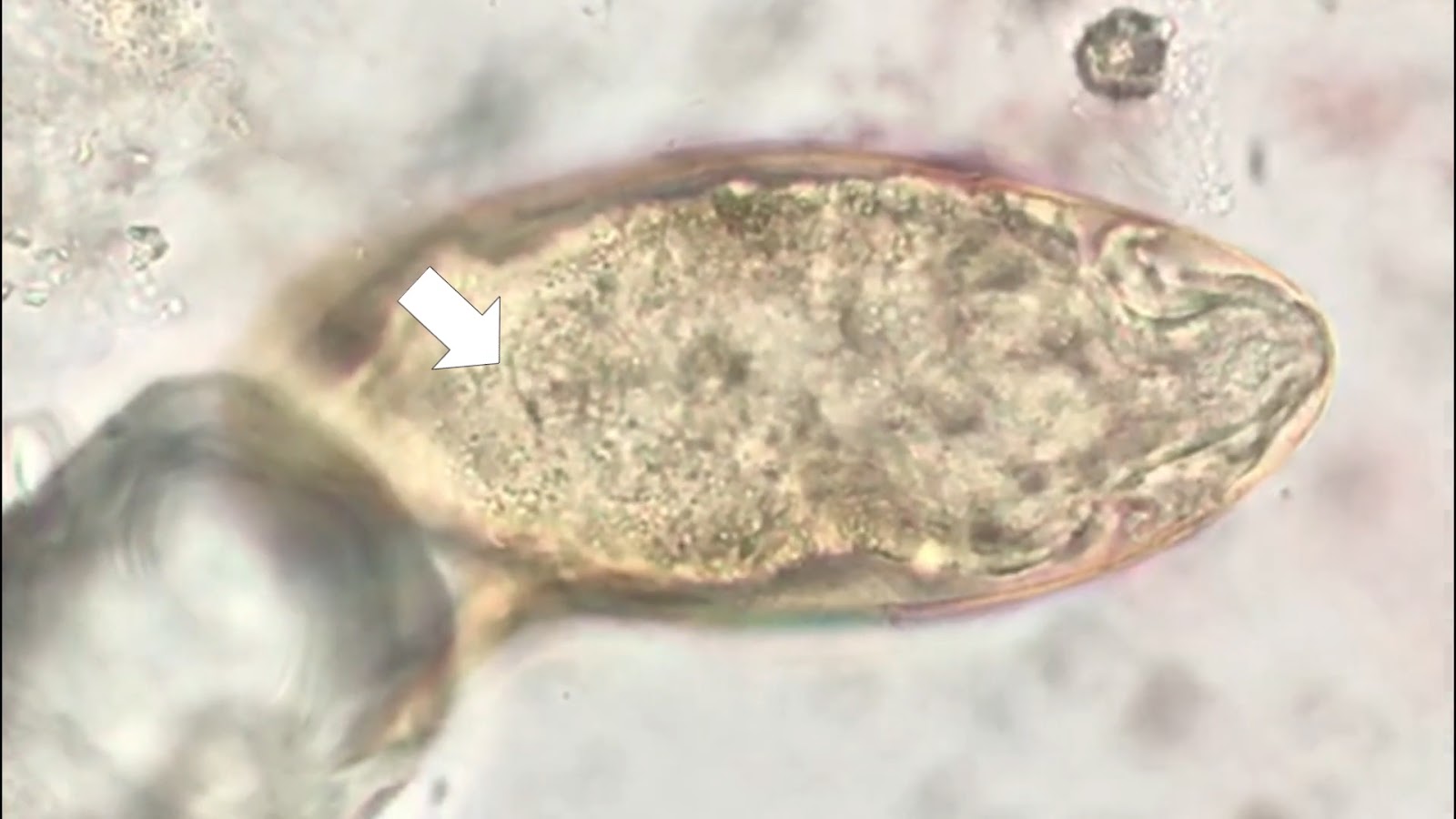

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 769: Live Schistosoma mansoni ova. Note the motile miracidium with its characteristic 'flame cell' - a specialized cell that is part of its excretory system, characterized by a flickering, flame-like movement of cilia which helps to expel waste products from the egg (see image below, and be sure to check out the video HERE.

The following excellent discussion is written by our guest author, Dr. Azra Hasan:

Everyone rightly recognized the oval egg with a” lateral spine”, the hallmark feature of Schistosoma mansoni.

Sometimes, it may be necessary to tap the coverslip to move the eggs; the lateral spine may not be visible if the egg is turned on its side. In very light or chronic infections, eggs may be tough to detect in stool; therefore, multiple stool examinations may be required and a biopsy and/or immunologic tests for antigen or antibodies help diagnose infection in these patients.

Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharziasis) spreads when people come in contact with freshwater contaminated by microscopic swimming cercariae released from infected snails. These cercariae penetrate intact skin and mature into adult worms as shown in the life cycle below. Schistosoma mansoni is endemic in Africa, South America, and the Caribbean. Humans are the definitive host and snails (Biomphalaria spp.). are the intermediate hosts. Adult worms reside in blood vessels of the intestines, laying eggs that trigger inflammation, fibrosis, and organ damage.

Clinical features

- Acute:

- Cercarial dermatitis follows skin penetration by cercariae. Stronger reactions may be seen in previously-sensitized hosts.

- Katayama fever is characterized by fever, cough, malaise, and diarrhea (Acute hypersensitivity reaction to the migrating larvae of S. mansoni, also seen in S. japonicum and S. mekongi)

- Chronic:

- Eggs are deposited in the mesenteric venous system and enter the intestinal wall and liver where they trigger an eosinophilic granulomatous host response, resulting in bloody diarrhea.

- While some eggs are excreted in the stool, many remain trapped in the tissue.

- Over time, chronic inflammation leads to fibrotic changes in the liver, with rigid portal veins, and portal hypertension with hepatomegaly.

- Rarely, schistosomiasis may present as neuroschistosomiasis (seizures, paralysis) due to ectopic eggs (usually associated with S. japonicum).

Fun Facts:

- Schistosoma is an ancient foe. Schistosoma eggs were found in 3000-year-old Egyptian mummies!

- Clingy Couple: We have seen the female worm residing in the male’s gynecophoric canal. Did you know this is a lifelong “embrace”?

- Undercover agent: These parasites coat themselves in human proteins to hide from the immune system.

- Egg factory: A female S. mansoni will produce ~300 eggs per DAY

Treatment:

Praziquantel is the gold standard. Oxamniquine is effective only against S. mansoni. Resistance to both these drugs has been reported. Early treatment prevents portal hypertension and related complications

Prevention with improved sanitation and avoiding wading in insanitary water, is better than cure! (Praziquantel kills adult worms but not immature larvae- It is important to note that If treatment starts early, always follow up with retreatment).

Salmonella-schistosome syndrome: When a secondary bacterial infection (usually Salmonella) occurs, anti-schistosome and antibacterial therapy should be given together; the disease remains if the schistosome is not treated simultaneously.

Some interesting case reports:

- Ectopic Eggs: Hepatic granulomas mimicking cancer in a Brazilian man (DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1436).

- Cardiac Schistosomiasis: A rare case of a 25-year-old man in Ethiopia with chest pain and heart failure was found to have S. mansoni eggs in myocardial tissue during autopsy. (PMID:32534906)

- Schistosoma Appendicitis- A case report of a 12-year-old Kenyan boy with acute appendicitis who had his appendix packed with S. mansoni eggs. (PMID 34840930)

- Pulmonary Hypertension- A 35-year-old Brazilian woman with chronic cough and fatigue had S. mansoni eggs in lung biopsies, leading to severe pulmonary hypertension DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2019.PA5392

- The Traveler’s Nightmare- A German backpacker developed acute neuroschistosomiasis after swimming in the Nile. MRI showed spinal cord inflammation from ectopic eggs! (PMID:29232415)

- Rectal Prolapse in a Child: A 4-year-old Ethiopian girl with chronic rectal prolapse had S. mansoni eggs in rectal biopsies. Parasites weaken tissues over time! (PMID:31462942)

- Paste the PMID number in PubMed for full-text articles

- Type ‘Schistosoma’ in the search bar of this blog and walk through the pages for more images and reads.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)