It was hard to get a still shot of this little arthropod:

Monday, March 26, 2018

Case of the Week 487

This week's case just came through my lab. The video and photos are courtesy of my excellent technical specialist, Heather Rose. Identification?

It was hard to get a still shot of this little arthropod:

It was hard to get a still shot of this little arthropod:

Sunday, March 25, 2018

Answer to Case 487

Answer: Cimex lectularis, or as Sheldon Campbell said, "Eew, bedbug!".

Eew, indeed. As someone who has been in hotel beds more than my own recently, I have perfected the 'bed bug check' of the hotel room. I have been fortunate so far NOT to have found any of these little pests in my hotel room. I am now on my way to Belize for a vector-borne disease capacity-building project and hope that the trend continues.

Thanks to William Sears and Florida Fan who shared some nice stories about C. lectularis, and its cousins, the bat bugs (check them out in the comments section).

Blaine also helpfully pointed out that you *might* be able to see the ecdysial scar on the pronotum, which would indicate that this is a nymph rather than adult female as I had originally indicated. I believe he is correct and so I took our my description of gender from the initial case description.

Eew, indeed. As someone who has been in hotel beds more than my own recently, I have perfected the 'bed bug check' of the hotel room. I have been fortunate so far NOT to have found any of these little pests in my hotel room. I am now on my way to Belize for a vector-borne disease capacity-building project and hope that the trend continues.

Thanks to William Sears and Florida Fan who shared some nice stories about C. lectularis, and its cousins, the bat bugs (check them out in the comments section).

Blaine also helpfully pointed out that you *might* be able to see the ecdysial scar on the pronotum, which would indicate that this is a nymph rather than adult female as I had originally indicated. I believe he is correct and so I took our my description of gender from the initial case description.

Monday, March 19, 2018

Case of the Week 486

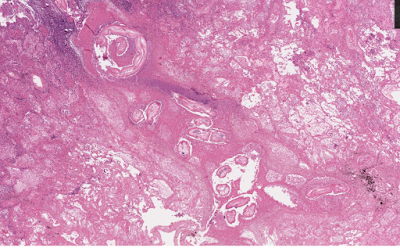

For this week's case, I'm going to take advantage of whole slide imaging technology via the cloud. The patient is a middle-aged male smoker from the southern United States who presented with shortness of breath, and imaging revealed a lung nodule. Because of concern for malignancy, the nodule was excised and sent to pathology for analysis. Here is a representative image of the nodule:

Click HERE to zoom in and explore this slide! You don't need any special password or software to view the case.

Diagnosis?

Bobbi

Click HERE to zoom in and explore this slide! You don't need any special password or software to view the case.

Diagnosis?

Bobbi

Sunday, March 18, 2018

Answer to Case 486

Answer: Dirofilaria sp., most likely D. immitis, given the location in the lung.

As Blaine pointed out, this case is unusual in that it features an adult rather than larval worm, as evidenced by the presence of reproductive organs. While it's not uncommon to see adult Dirofilaria in subcutaneous lesions (e.g. caused by D. tenuis), it's very uncommon (but not unheard of) to see adults in the lung. Some of the diagnostic features are highlighted in the image below.

Thanks to everyone who gave the whole slide imaging technology a 'whirl', even if histopathology is not your area of expertise.

As Blaine pointed out, this case is unusual in that it features an adult rather than larval worm, as evidenced by the presence of reproductive organs. While it's not uncommon to see adult Dirofilaria in subcutaneous lesions (e.g. caused by D. tenuis), it's very uncommon (but not unheard of) to see adults in the lung. Some of the diagnostic features are highlighted in the image below.

Thanks to everyone who gave the whole slide imaging technology a 'whirl', even if histopathology is not your area of expertise.

Monday, March 12, 2018

Case of the Week 485

This week's case is donated by Dr. Luis Fernando Solórzano Álava from Ecuador. The 'patient' is not a human, but rather an Ecuadorian snail. However, the parasite shown is indeed very pathogenic to humans and has a predilection for the central nervous system.

Any thoughts on its identification?

You can also see the video HERE.

Any thoughts on its identification?

Sunday, March 11, 2018

Answer to Case 485

Answer: Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the rat lungworm

As many of you mentioned, the clues to the identification of this parasite are the characteristic morphology of the larvae, the host (snail), and the predilection of the parasite for the human central nervous system (CNS). A. cantonensis can infect snails and slugs, which if accidentally ingested, can lead to debilitating, even fatal, eosinophilic meningitis in humans when the immature worms migrate to the CNS and die. Human infection can also be acquired through ingestion of infected paratenic hosts such as crabs and fresh water shrimp, and may potentially be acquired through ingestion slug/snail slime containing L3 larvae on inadequately-washed vegetables.

Although this infection was first identified in Asia, it has spread throughout the Pacific basin, and is also found in parts of Africa, the Caribbean, and Ecuador. Florida Fan points out that the related organism, A. costaricensis, causes intestinal angiostrongyliasis, and is found in parts of South and Central America. Most cases of A. costaricensis infection are reported from Costa Rica

As many of you mentioned, the clues to the identification of this parasite are the characteristic morphology of the larvae, the host (snail), and the predilection of the parasite for the human central nervous system (CNS). A. cantonensis can infect snails and slugs, which if accidentally ingested, can lead to debilitating, even fatal, eosinophilic meningitis in humans when the immature worms migrate to the CNS and die. Human infection can also be acquired through ingestion of infected paratenic hosts such as crabs and fresh water shrimp, and may potentially be acquired through ingestion slug/snail slime containing L3 larvae on inadequately-washed vegetables.

Although this infection was first identified in Asia, it has spread throughout the Pacific basin, and is also found in parts of Africa, the Caribbean, and Ecuador. Florida Fan points out that the related organism, A. costaricensis, causes intestinal angiostrongyliasis, and is found in parts of South and Central America. Most cases of A. costaricensis infection are reported from Costa Rica

Monday, March 5, 2018

Case of the Week 484

It's the first of the month again - time for a case from Idzi Potters and the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp!

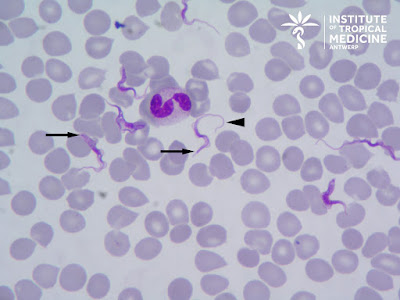

The patient is a frequent traveler who recently returned from Kenya where he participated in a game tracking excursion. He now presents with high fever, malaise and headache. The following were seen in a preparation of unfixed blood:

You can also see the video on YouTube: https://youtu.be/IGadYEsc5rA

A Giemsa-stained thin blood film was also performed and showed the following:

Identification?

The patient is a frequent traveler who recently returned from Kenya where he participated in a game tracking excursion. He now presents with high fever, malaise and headache. The following were seen in a preparation of unfixed blood:

You can also see the video on YouTube: https://youtu.be/IGadYEsc5rA

A Giemsa-stained thin blood film was also performed and showed the following:

Identification?

Sunday, March 4, 2018

Answer to Case 484

Answer: Trypanosoma brucei

This is most likely T. brucei rhodesiense based on:

Be sure to check out the video which show the characteristic 'auger' like motility of the trypomastigotes (i.e. rotating along its long axis).

Thanks to everyone who wrote in with the excellent comments. A lot of good points were raised by all. Ali Mokbel mentioned that we can't exclusively rule out T. b. gambiense, given that the patient is a frequent traveler and may have been to West Africa. Idzi also reminded us that the trypomastigotes of T. brucei are indistinguishable from those of T. rangeli, a non-pathogenic New World trypanosome which can occasionally infect humans. Fortunately, we can tentatively rule out these other species/subspecies based on the very high parasitemia and patient's symptoms. If there was any question about the identification (e.g. based on the patient's travel history), sub-species determination using PCR could be performed.

Finally, LS reminded us of the importance of determining whether the patient had central nervous system involvement since that would change the therapy. If suspected, a lumbar puncture could be performed to look for trypomastigotes.

For our students of parasitology, the following contains some general information about trypomastigotes, the most trypanosome stage seen in peripheral blood. Trypomastigotes are extracellular, unlike Plasmodium parasites, and may be seen 'swimming' between the red blood cells as in this case (check out Idzi's really cool video!). Although they have a somewhat 'worm-like' appearance, they are protozoa (not helminths), and can be easily differentiated from microfilariae by their small size (14 to 33 micrometers in length). They have a kinetoplast at their posterior end (arrows in image below) and a centrally located nucleus. A flagellum arises from the basal body (associated with the kinetoplast) and travels along the long axis of the trypomastigote as an undulating membrane. It projects from the anterior end as a free flagellum (arrow head, below), and provides the characteristic 'auger-like' motility of the trypomastigote.

Note that the flagellum is at the anterior end of the trypomastigote, and not the posterior as many would expect!

The size of the kinetoplast is very useful for differentiating the trypomastigotes of T. brucei/T. rangeli from those of T. cruzi. As you can see from the image below, the kinetoplast of T. cruzi is much larger:

This is most likely T. brucei rhodesiense based on:

- The patient's recent travel to Eastern Africa (Kenya),

- His participation in a game tracking excursion (classic history given that wild ungulates are the reservoir for this subspecies),

- His rapid onset of symptoms, and

- The very high (!) parasitemia

Be sure to check out the video which show the characteristic 'auger' like motility of the trypomastigotes (i.e. rotating along its long axis).

Thanks to everyone who wrote in with the excellent comments. A lot of good points were raised by all. Ali Mokbel mentioned that we can't exclusively rule out T. b. gambiense, given that the patient is a frequent traveler and may have been to West Africa. Idzi also reminded us that the trypomastigotes of T. brucei are indistinguishable from those of T. rangeli, a non-pathogenic New World trypanosome which can occasionally infect humans. Fortunately, we can tentatively rule out these other species/subspecies based on the very high parasitemia and patient's symptoms. If there was any question about the identification (e.g. based on the patient's travel history), sub-species determination using PCR could be performed.

Finally, LS reminded us of the importance of determining whether the patient had central nervous system involvement since that would change the therapy. If suspected, a lumbar puncture could be performed to look for trypomastigotes.

For our students of parasitology, the following contains some general information about trypomastigotes, the most trypanosome stage seen in peripheral blood. Trypomastigotes are extracellular, unlike Plasmodium parasites, and may be seen 'swimming' between the red blood cells as in this case (check out Idzi's really cool video!). Although they have a somewhat 'worm-like' appearance, they are protozoa (not helminths), and can be easily differentiated from microfilariae by their small size (14 to 33 micrometers in length). They have a kinetoplast at their posterior end (arrows in image below) and a centrally located nucleus. A flagellum arises from the basal body (associated with the kinetoplast) and travels along the long axis of the trypomastigote as an undulating membrane. It projects from the anterior end as a free flagellum (arrow head, below), and provides the characteristic 'auger-like' motility of the trypomastigote.

Note that the flagellum is at the anterior end of the trypomastigote, and not the posterior as many would expect!

The size of the kinetoplast is very useful for differentiating the trypomastigotes of T. brucei/T. rangeli from those of T. cruzi. As you can see from the image below, the kinetoplast of T. cruzi is much larger:

Monday, February 26, 2018

Case of the Week 483

This week's case was donated by Dr. Lars Westblade. The patient 'coughed' up the following worm (which was still moving!) after approximately 1 month of intermittent hives.

The posterior end was damaged unfortunately, but here is the anterior end:

What is your differential diagnosis?

The posterior end was damaged unfortunately, but here is the anterior end:

What is your differential diagnosis?

Sunday, February 25, 2018

Answer to Case 483

Answer: Probable anisakid (Anisakis sp., Pseudoterranova sp., or Contracaeceum sp.)

There was a lot of great discussion on this case! While we can't definitively rule out a migratory immature Ascaris lumbricoides (crawling up from its usual intestinal location), the size of the worm, morphology, and patient history are most consistent with this being an anisakid larva. Anisakiasis occurs in humans following consumption of undercooked fish or seafood containing coiled anisakid larvae. The larvae cannot mature in humans but still have the potential to cause significant problems for their unintended human host. In the 'best case scenario', the larva dies and is passed in stool. If seen by the patient, it may be submitted to the laboratory for identification. A less optimal scenario is what was seen in this case where the live larvae crawls up the esophagus and is 'coughed up' or expelled out of the mouth. While no doubt disturbing, this is still better than the alternative, in which the larva burrows into the gastric or intestinal mucosa, causing significant pain for the host. If the larva is not immediately removed, the patient may experience symptoms for an extended period of time until the larva dies and is absorbed by the host. Rarely, the larva will penetrate the wall of the stomach or intestine and enter the peritoneal cavity, wreaking further havoc. A final, but equally important, complication of exposure to anisakid larvae is development of an allergy to anisakid proteins. This can occur regardless of whether the larva is alive or dead. Sensitized individuals must avoid anisakid-infected fish or risk experiencing serious allergic, or even anaphylactic, reactions, upon re-exposure.

Anisakid larvae can be identified by a few features: they are ~3 cm in length, have 3 fleshy lips just like A. lumbricoides, and also have a very small 'boring' tooth on the anterior end (which can be very difficult to see). Some species also have a posterior spicule called a mucron which is easier to identify. Ascaris doesn't have a boring tooth or posterior mucron, so these are helpful features when seen. Unfortunately the posterior end was damaged during removal so we weren't able to examine it.

What I found to be very interesting about this case was the history of hives, suggesting an allergic reaction to the larva. The time frame of symptoms was also interesting - the patient experienced hives for ~ 1 month before expelling the worm, which indicates that either the larva was present all of that time without causing any gastrointestinal symptoms, or the patient had ongoing exposure to anisakids through his diet. I'd be curious to know - have any of my readers run into a similar case? This is actually the second case I've seen where the patient had been symptomatic for several weeks after presumed exposure and before expelling the larva. This leads me to think that some larva can exist in the host for weeks without burrowing into the gut lining. Please let me know what your experience has been!

There was a lot of great discussion on this case! While we can't definitively rule out a migratory immature Ascaris lumbricoides (crawling up from its usual intestinal location), the size of the worm, morphology, and patient history are most consistent with this being an anisakid larva. Anisakiasis occurs in humans following consumption of undercooked fish or seafood containing coiled anisakid larvae. The larvae cannot mature in humans but still have the potential to cause significant problems for their unintended human host. In the 'best case scenario', the larva dies and is passed in stool. If seen by the patient, it may be submitted to the laboratory for identification. A less optimal scenario is what was seen in this case where the live larvae crawls up the esophagus and is 'coughed up' or expelled out of the mouth. While no doubt disturbing, this is still better than the alternative, in which the larva burrows into the gastric or intestinal mucosa, causing significant pain for the host. If the larva is not immediately removed, the patient may experience symptoms for an extended period of time until the larva dies and is absorbed by the host. Rarely, the larva will penetrate the wall of the stomach or intestine and enter the peritoneal cavity, wreaking further havoc. A final, but equally important, complication of exposure to anisakid larvae is development of an allergy to anisakid proteins. This can occur regardless of whether the larva is alive or dead. Sensitized individuals must avoid anisakid-infected fish or risk experiencing serious allergic, or even anaphylactic, reactions, upon re-exposure.

Anisakid larvae can be identified by a few features: they are ~3 cm in length, have 3 fleshy lips just like A. lumbricoides, and also have a very small 'boring' tooth on the anterior end (which can be very difficult to see). Some species also have a posterior spicule called a mucron which is easier to identify. Ascaris doesn't have a boring tooth or posterior mucron, so these are helpful features when seen. Unfortunately the posterior end was damaged during removal so we weren't able to examine it.

What I found to be very interesting about this case was the history of hives, suggesting an allergic reaction to the larva. The time frame of symptoms was also interesting - the patient experienced hives for ~ 1 month before expelling the worm, which indicates that either the larva was present all of that time without causing any gastrointestinal symptoms, or the patient had ongoing exposure to anisakids through his diet. I'd be curious to know - have any of my readers run into a similar case? This is actually the second case I've seen where the patient had been symptomatic for several weeks after presumed exposure and before expelling the larva. This leads me to think that some larva can exist in the host for weeks without burrowing into the gut lining. Please let me know what your experience has been!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)