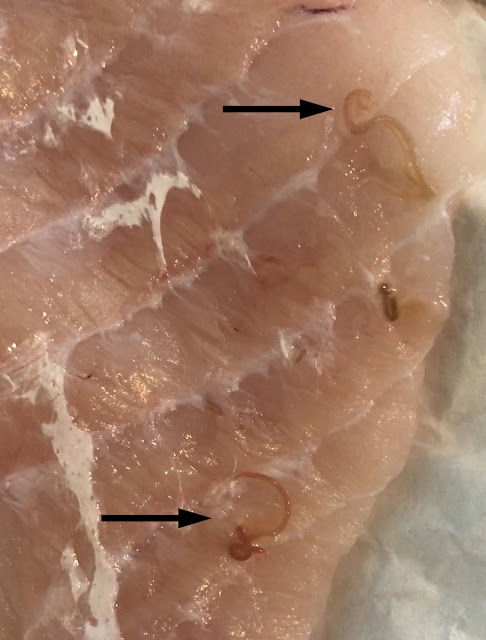

Answer to the Parasite Case of the Week 684: Anisakid L3 larvae

The following is our third and final discussion from our amazing guest author and 3rd year medical student, Hadel Go. I'm sure you will all agree that her discussions have been among the best we've ever had on this blog. Congratulations on the excellent work, Hadel!

_____________________

Worm cases are always my favorite because the comments are

either “They are so beautiful!!” (@Parasite_Power on Twitter) or “…That’s a

wholelottanope” (Valmik in the comments).

This is a nematode in the Anisakidae family, likely Pseudoterranova or Anisakis spp., the two most common cause of human anisakiasis, as many of you suggested. A third genus, Contracaecum, is also a possibility. Mario George Nascimento and Melinh Luong point out that its dark color implicates Pseudoterranova (vs Anasakis which is usually white/pink/red).

However definitive identification to the genus level requires closer inspection of the intestinal cecum and its positioning as mentioned by Idzi P. in the comments and seen in Case 563 which he donated.

Diagnostic features of Pseudoterranova and Anasakis

spp. include a “mucron… and 3 poorly formed anterior lips with a small boring

tooth” (see Case

157 and Case

557). The table below shows some varying characteristics between the two

more common culprits:

|

Larva |

Anisakis

simplex |

Pseudoterranova

decipiens |

|

Appearance |

White, milky |

Yellow-brown |

|

Dimensions |

19-36mm long;

0.3-0.6mm wide |

25-50mm,

0.3-1.2mm wide |

|

Other

features |

Blunt tail,

long stomach, Y-shaped lateral cords, no cecum |

Anteriorly

directed cecum |

LIFE CYCLE (CDC)

1. Marine mammals defecate into the sea releasing unembryonated eggs

2. Eggs become embryonated in water

3. L2 larvae form in eggs and hatch out

4. Free swimming L2 larvae are ingested by crustaceans and mature into L3

larvae in the hemocoel

5. Fish (any marine fish is susceptible) and cephalopods eat infected

crustaceans

6. Larvae migrate to mesentery and muscle tissues of the new host

7. L3 larvae are transferred from fish to fish until ingested by a marine

mammal

8. L3 larvae molt twice in the mammal and develop into adults which produce

eggs

Anisakiasis occurs when these parasites at the L3 larval stage are ingested

in raw or undercooked saltwater seafood. While some larvae will die following ingestion, or make their way up the esophagus into the oral cavity (much to the dismay of the human host!), they may also attach to the wall of the human esophagus,

stomach, or intestine causing damage or inflammation. Since humans are

incidental hosts, the anisakids do not mature into adults. Symptoms include

abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, distention, diarrhea, blood/mucus in stool,

and mild fever. If a patient is allergic to anisakids, rash, itching, angioedema, or

anaphylaxis can occur (even when the worms are dead). Complications include intestinal obstruction,

peritonitis, and intestinal perforation. Severe immune response following

penetration of intestinal tissue can resemble Crohn’s disease.

These roundworms can be visualized and removed with an

endoscope, confirming the diagnosis. If not removed, they will eventually die and can cause

inflammation. A biopsy can reveal an eosinophilic granuloma containing the dead

nematode. Endoscopic or surgical removal of the parasites is curative. Treatment

with albendazole has been used successfully to kill the worms, although not FDA

approved for anisakiasis. Unembedded worms are usually eliminated by the body within 3

weeks.

Avoid infection by following one of these FDA

recommendations which kills the parasite:

- Cook seafood (145°F or above)

- Freeze at -4°F or below for 7 days

- Blast freeze at -31°F or below until solid and store at -31°F or below for 15

hours

- Blast freeze at -31°F or below until solid and store at -4°F for below for 24

hours

I’ve often been asked if I eat sushi and sashimi knowing the

prevalence of these worms… and the answer is YES, I love Japanese cuisine and I

eat them regularly. All fish intended for raw consumption in the US are

required by the FDA to be frozen as stated above so they should be safe. The

dead parasites may still be on the tissue, but they won’t be infectious. I would

however be more hesitant to eat raw or undercooked fish when traveling to

places where there are less stringent regulations. Ask for sushi/sashimi grade

fish and use your best judgement!

TAXONOMY

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Nematoda (roundworms)

Order: Rhabditida

Family: Anisakidae

Read more:

1. CDC -

Anisakiasis

2. Anisakidosis:

Perils of the Deep | Clinical Infectious Diseases | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

3. Anisakis,

Something Is Moving inside the Fish - PMC (nih.gov)

4. Assessing

the risk of an emerging zoonosis of worldwide concern: anisakiasis - PMC

(nih.gov)

Thank you @leon_metlay on Twitter for sharing this paper:

Intestinal

anisakiasis. Report of a case and recovery of larvae from market fish - PubMed

(nih.gov)

This is my third and final post as a guest blogger here and

I’d like to thank Dr. Bobbi Pritt for the opportunity to learn more about these

creatures and share what I’ve learned with you all!

7 comments:

Wonderful work!

Once more a beautiful and very educational explanation!

Many thanks Hadel! Hope to hear more from you in the future!

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/imj.13786

The otherside of delicacies : "The Sushi's Paradigm", thank u Prof. and Hadel Go!

Congratulations for this very interesting case!

👏👏👏

If anyone is interested in the etymology of the name, Pseudoterranova, please see the explanation in Emerging Infectious Diseases:

Norton SA, Gibson DI.

Etymologia: Pseudoterranova azarasi [letter].

Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17(9): 1784.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3358089/

Here is an extract from that letter:

... Although the Greco-Latin amalgam, Pseudoterranova, translates to “false new earth,” the generic name of the organism refers to the ship, the Terra Nova, which Robert Falcon Scott captained en route to Antarctica exactly 100 years ago in his ill-fated attempt to be the first person to reach the South Pole.

During the Antarctic summer of 1911–12, while Scott and 4 companions trudged toward the South Pole, the ship’s surgeon, Edward Leicester Atkinson, who remained with the Terra Nova, dissected polar fish, birds, and sea mammals, looking for parasites. Atkinson found an unusual nematode in a shark, and in 1914, he, along with parasitologist Robert Thomson Leiper of the London School of Tropical Medicine, commemorated the ship by conferring the name Terranova antarctica upon this newly discovered creature (2).

The genus Pseudoterranova was established by Aleksei Mozgovoi in 1951 for a somewhat similar nematode obtained from a pygmy sperm whale. Pseudoterranova azarasi, the subject of the Etymologia, was originally described in 1942 as Porrocecum azarasi, but recent molecular work, as described by Arizono et al. (3) and Mattiucci and Nascetti (4), showed that this nematode is part of a large species complex within Pseudoterranova. Thus, it has been transferred to this genus as part of the P. decipiens species complex.

The nomenclatural specifics are complex and arcane. However, in this centennial year of the Terra Nova expedition, we think it is worthwhile to remember the historic origins of these names....

Post a Comment